Design and Nature Reimagined: The universe beneath our feet (Part 1)

When I first moved to the Pacific Northwest, I was fascinated by its climate. Oregon is part of a large temperate rainforest that sits along the northwest coast of North America, stretching all the way up through Canada and down through part of California. I had never seen ferns like we have in the Pacific Northwest. I’d never known that moss was actually many, many shades of green and varied in length, softness, and patterns. And never had I seen mushrooms like we have here. On my daily walk there’s a house that has some mushrooms the size of dinner plates. I watch the turkey tail mushroom growing on my maple, and see the little whitecaps coming up through my leaf mulch. Fungi are everywhere, and the more I’ve seen it the more entranced I’ve become. So let’s look at how fungi works, and how we might learn from it. Part 1 will include cool fungus facts (a phrase I never thought I’d say), and Part 2 will reimagine how we might learn from fungus.

What is fungi?

First off, fungi isn’t a plant. Fungi do not produce chlorophyll and they can’t create their own food through photosynthesis. Because of this, fungi have to get nutrients from organic substances. Additionally, they have a cell structure that differs from plants. Fungi cell walls are made of chitin, where as plant cell walls are made of cellulose. Chitin is the same substance that you find on arthropods like arachnids, insects, centipedes / millipedes, and crustaceans (shrimp, crab, lobster etc.) So, at a cellular level, fungi most closely resemble animals. But, they’re also not animals. The way they digest food externally first, and then absorb it into themselves. Plus they have vegetative growth, where they grow from the tips of filaments that then make up their bodies. So, fungus belongs to its own Kingdom Fungi (sounds yummy) that also includes molds, puffballs, mildew, and yeast. And fungus is everywhere. Literally. It’s in the soil, in our bodies, and in the air. In fact, you’re breathing it in right now. On an average day you’ll breathe in between 1,000 and 10 billion (with a B) mold spores everyday. It’s literally… everywhere.

Fungi Communication

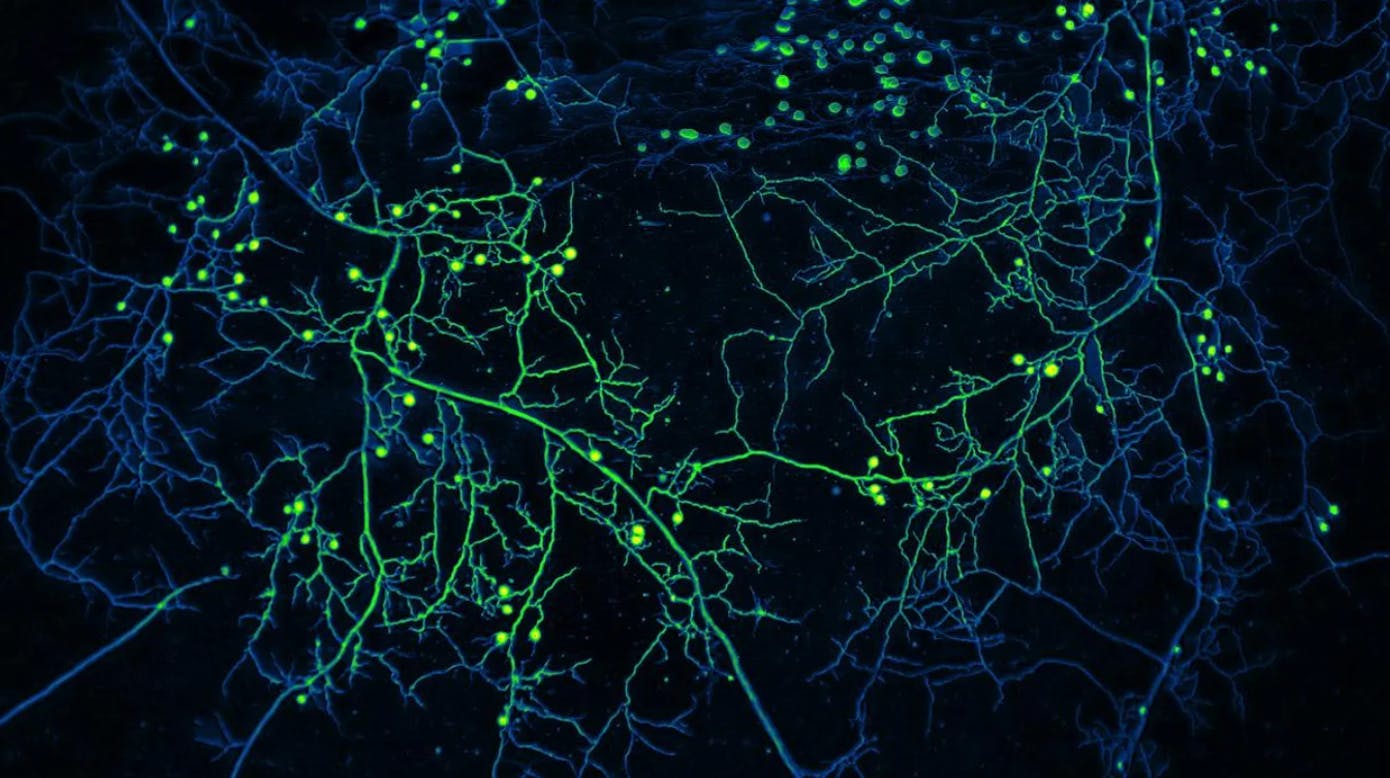

Fungi communicates with itself and with the plants they connect with. A mycelial network has more pathways than the brain and shares the same design as a computer network. They use trees as their pathways of communication. Fungi are also present in many plant roots (over 80%), creating a symbiotic relationship called mycorrhizae. When looked at closely you can see the fungi woven around and through the root system, or the fungi may create a sheath around the root to protect it. This relationship between plant and fungi is mutualistic because the fungi improve the plant’s ability to acquire nutrients (like phosphate or minerals) by extending the surface area of soil a plant can pull nutrients from. It does this through long extensions called hyphae, which are long branching filaments. In return for this help, the plants distribute give more sugar to the fungi to help it live and grow.

In addition to that, it’s been noted that the fungi can remove heavy metals from the area surrounding the plants, and even provide antibiotic compounds to protect the plants from attackers. Similarly, if a tree knows that there are pests in the area, the mother tree will push her child trees further out to avoid the pests.

All of this happens by communicating through the mycelial network. The plants and trees have to recognize there is a problem, decide how to confront the problem, and communicate the solution through the network to solve the problem. While the network sends sugars, nutrients, and minerals to the plants and trees like I mentioned above, it also uses this dense network as a way to communication pathway; and so far it looks like almost all plants are connected to this network.

Well what has fungi done for me lately?

And of course we’re taking a very plant-centric view here, when really I think we should be taking a fungus-first viewpoint. But, I know you’ve got to be thinking, it… how does fungus actually, materially, impact you. Beyond the fact that it’s the basis for healthy soil where all your food comes from… but in addition to that I guess, what does it do for you, personally? An obvious thing comes to mind first; mushrooms! Either the tasty kind or the recreational kind (psilocybin is a whole other fascinating topic). Plus you’ve got fungi to thank for lots of tasty breads, wines, cheese, and beer. You can also thank them for penicillin and a host of other antibiotics and medicines, and the fact that they live in your gut microbiome and work alongside bacteria to keep you healthy. What I’m trying to say is that fungi is everywhere, and it’s deeply ingrained in our lives.

70% of CO2 from plants gets pulled back into the soil and the carbon ends up in fungal cell walls, where it’s stored. This fuels the microbial community. Microscopic worms that live within the soil, called nematodes, are an important part of this ecosystem and live within the soil as well. The CO2 that’s stored in the soil and mycelial network also plays a role in both the lifecycle and feeding habits of nematodes. Ultimately, the mycelium stabilizes the carbon storage.

But, perhaps the biggest thing that they do is something we’ve likely never noticed. They consume everything that’s died. Yep. Without fungus, the earth would be covered in all the stuff that’s died over the course of the Earth’s lifetime. Fungus composts those organisms and returns them to the the soil, water, and air. They are the world’s recycler. Fungi help create life, by helping us through death.

As far as I can see, fungi are intelligent: they seek out food, they protect themselves from danger, they create mutualistic relationships, and they problem solve. In fact, they’re some of the most efficient puzzle solvers we’ve ever seen. We’ll talk more about those puzzles, problem solving, and fungus next time!