Neuroscience, Behavior, and Anxiety: Growing once you're grown

It started when I was 16. At first it was some minor dissociation once in a while when I looked into a mirror. As time progressed that was typically followed by a panic attack which ended with me crying on the floor, convinced I was going to die or that the feeling of not being me, would never go away.

Things slowly got better as I got older and went to therapy. The dissociation went away. Then the panic attacks, too, for the most part. I didn’t have any panic attacks until the summer and early fall of 2018. The first in almost 10 years. I learned quickly that when I got too much bad stress and not enough good stress my body’s initial response was downright panic.

But throughout everything, the anxiety remained, sitting in the back of my mind, muttering doomsday prophecies.

“What are you doing? Don’t do that, something bad will happen. You know the world is burning right? We’re all going to burn right along with it. Nothing you can do to stop it.” And sometimes, it’s just a constant screaming in the back of my mind. Not about anything in particular. Just basic, run of the mill terror.

Since I was little, I’ve had the sense that nothing is guaranteed. I’m adopted, and grew up knowing that I was adopted. I had a wonderful childhood, but at least for me, being adopted really gave me a sense of not being fully connected. There was a sense that I just kind of ended up in my family. So I realized fairly early that you don’t know what’s going to happen and a decent portion of what does happen is luck. I lucked into a loving, caring family. It was lucky that my biological mother was willing to give me up for adoption. I was lucky that I’ve been generally healthy my whole life. None of these things are ever guaranteed.

And I think realizing there is no guarantee, combined with seeing family illness and death when I was young solidified this anxiety pretty early. It was also something I learned from my family. So even though I don’t remember the illness and deaths being very traumatic, I do know that I ended up being pretty anxious, a lot of the time, and usually about my health. Anxiety has a way of seeping in through the cracks and filling up the space.

Anyway I’ve spent lots of time going to therapy trying to lock that anxiety away in the back room of my brain. Somewhere it can’t get out. Somewhere I can’t hear it.

And because of this, I’ve always been fascinated with human behavior, psychology, and neurology. I’ve always hoped that one day I could kick this anxiety habit.

I say habit not because I think it’s trivial, but because anxious patterns really do wear a pathway in your brain, meaning that you’ll fall into anxiety more and more easily because it’s a known and reinforced pathway.

So rather than trying to scrub the old path away, I’ve been trying to create a new path that’s better. I recently listened to Dr. Andrew Huberman on a podcast with Rich Roll.

I learned so much I ended up taking notes. Many, many notes. And I want to share what I learned with you.

The way Dr. Huberman applied neuroscience and brain chemsitry on top of techniques that I’d already learned from people like Carol Dweck, Daniel Kahneman, and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, was really helpful.

It was kind of like the groundcover that pulls the whole garden together. Or the pathway that connects the garden. (Fix the metaphor here. I don’t know. It’s not right.)

Here’s what I learned

I’d always assumed that anxiety was just a habit that you could unlearn. I’d assumed you needed to just carve new pathways. Turns out I was right… sort of.

What I didn’t know was that we’ve got something called the autonomic nervous system which controls a lot of your subconscious bodily functions: heart rate, digestion, respiratory rate, pupillary response, urination, and sexual arousal.

And even though you’re not actively controlling it through your thoughts, there are ways to influence thoughts through action. The feeling of anxiety starts in the autonomic nervous system.

Anxiety vs. calm

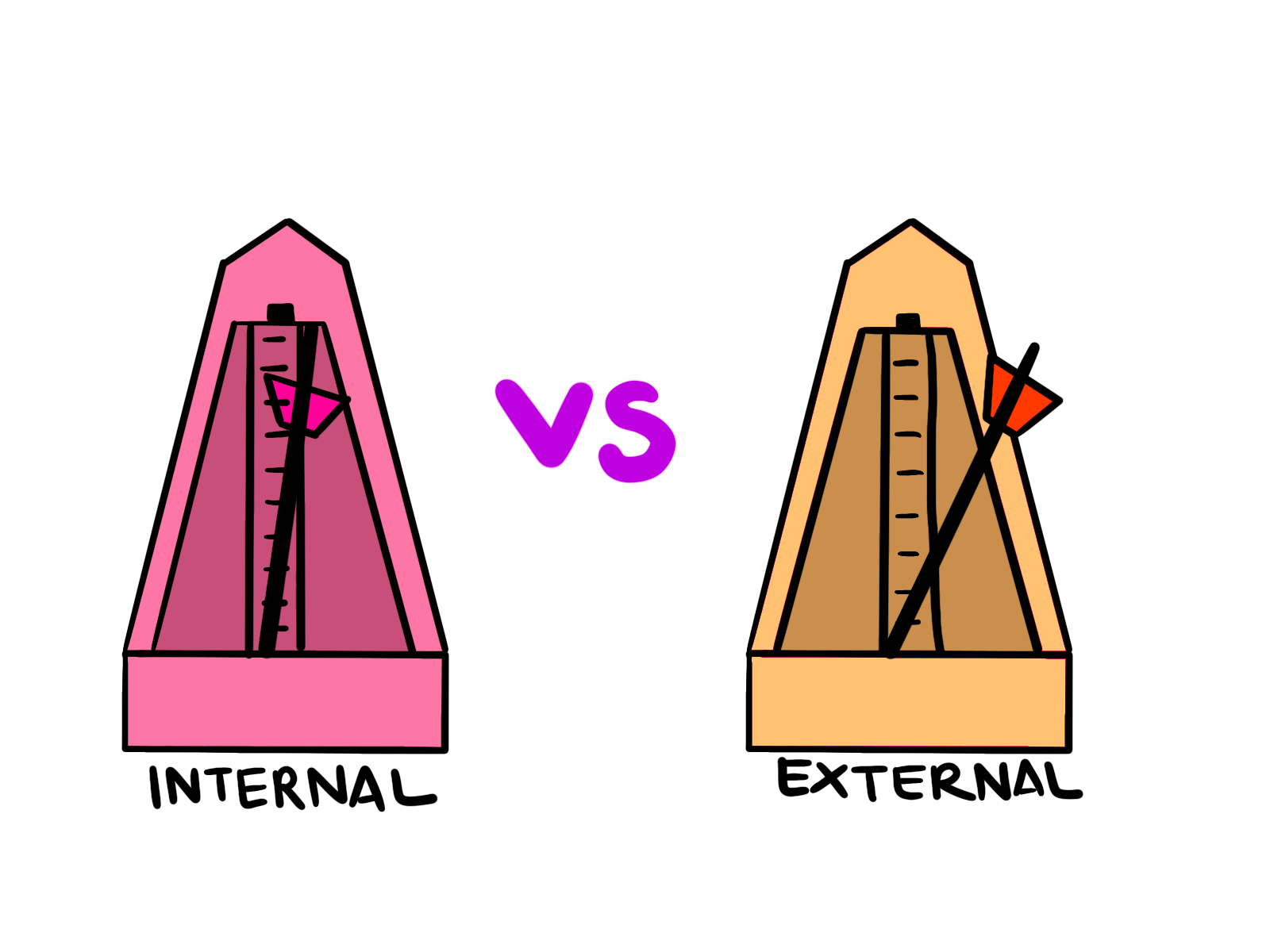

As with all things in nature, our bodies are trying to find homeostasis or balance between what’s happening internally and what’s happening around us, externally.

This is partly why our perception of time shifts depending on how we feel. When you’re anxious about being late for something, having to stand in line to get coffee feels endless. When you’re relaxed on a Saturday morning with nowhere to be, the same line and wait hardly even registers.

This is because we’ve got an internal metronome that’s constantly trying to sync up with our environment, the external metronome. When the two are out of balance, we feel uncomfortable and that discomfort leads to anxious feelings.

Along these same lines, we start to feel anxious when our old fears start creeping into our thoughts. If you’ve learned about or have tried meditation, there’s a focus on just letting the thoughts pass by. And this can be really helpful for calming yourself down.

Don’t try to get rid of old thoughts. Don’t try to stop thinking about things that bother you. Get new thoughts instead. Add on to what you’re already experiencing. If you’re thinking, “I hate all the noise coming from the cars on the street,” instead of trying to stop thinking that, find a sound you do like and add on. “I hate all the nose coming from the cars on the street, but the chimes in the trees sound lovely.”

Not only does this reframe what you’re thinking, but it allows you to have that feeling without trying to shove it down. Shoving it out of the way just won’t work in the long term. Trying to shove those thoughts out of the way makes us ruminate on them. If I tell you “don’t think of a pink elephant,” what are you immediately picturing right now?

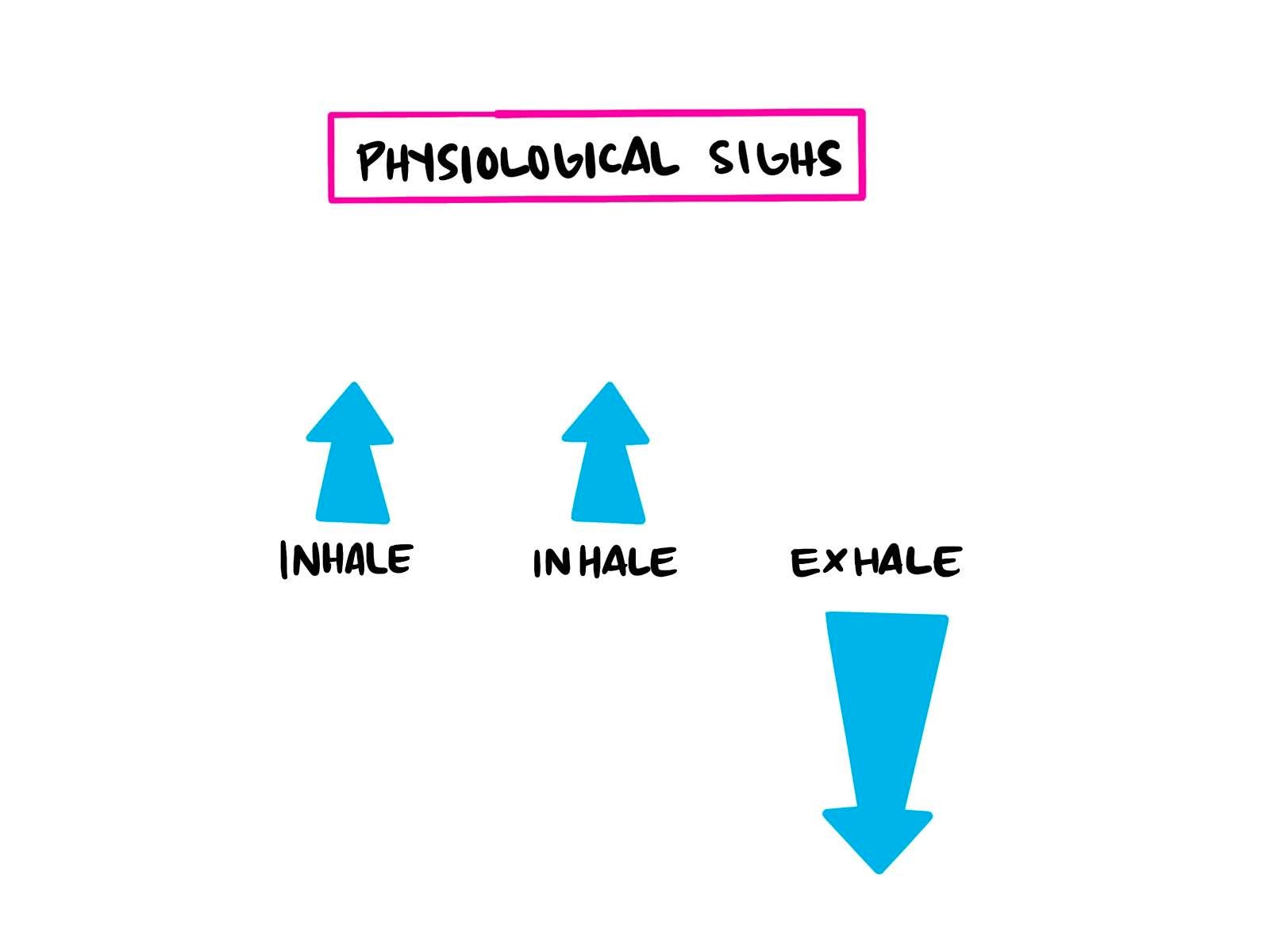

Another physical response we have when we get anxious is that our breathing changes. We hold our breath. We tense up. We clench our jaw. This leads our autonomic nervous system to go kind of haywire. You can get dizzy, feel short of breath, your heart feels like it’s pumping out of your chest. While there are actual illnesses that can cause this, it’s also a stress response from our nervous system.

Physiological sighs for calming yourself can help resolve this. Again, you can’t calm yourself with thoughts, but you can calm yourself with action. To do a physiological sigh, you take two short breaths in, hold your breath for a count, and then exhale. These sighs help open up your lungs to let more air in, and also frees up the diaphragm so that you can breathe better. The additional oxygen and regulation of your breathing helps calm your autonomic nervous system, and your anxiety.

How we get motivated and stay motivated

I don’t know about you, but dealing with anxiety can also mean that it’s hard for me to get motivated to do things. I’m so anxious I can’t focus so I can’t get started.

In order for us to get motivated to do anything, our body needs to feel some form of urgency. Urgency often shows up as a feeling of agitation. Our body and mind is yelling at us to DO SOMETHING to relieve the feeling. For example, when you’re hungry (or hangry, if you’re me), you get uncomfortable and you want to relieve that feeling.

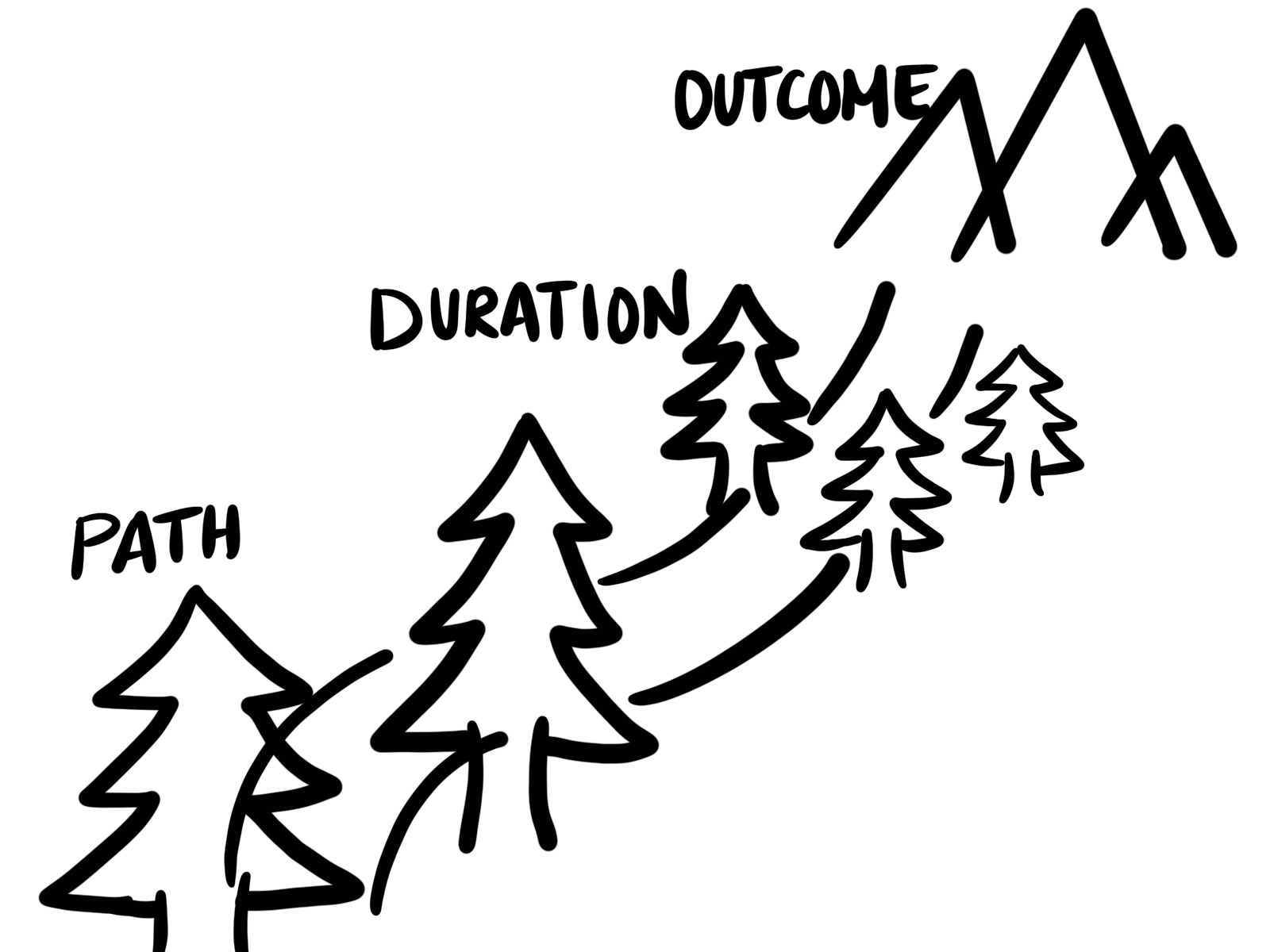

Once you feel that urgency, your brain immediately starts creating a plan to resolve the feeling. To do that our brain assesses path, duration, and outcome. This becomes our motivation. How do I get food? How long will it take me to get food? When will I get to eat?

The urgency and discomfort you feel is what causes you to forage around in the cupboard, desperately searching for the bag of tortilla chips you’re pretty sure you finished two days ago. All that rummaging is thanks to your brain feeling urgency, assessing a path to get you fed, and figuing out how long it’s going to take before you get to those sweet, sweet chips… and maybe some salsa.

But how do we get the energy to do this? We’ve all felt so tired that we slap some cheese on some bread and call it dinner. I hope. Or maybe that’s just me. In order to stay motivated our body needs two things: focus and sleep.

Without focus, we can’t concentrate on the path, duration, and outcome to relieve our urgency. And without sleep our brain chemistry gets all messed up and we can’t focus! And that’s how we end up leaning against the counter munching on an old hamburger bun with a Kraft singles on it, hungry for something more but too exhausted from it all to do anything else.

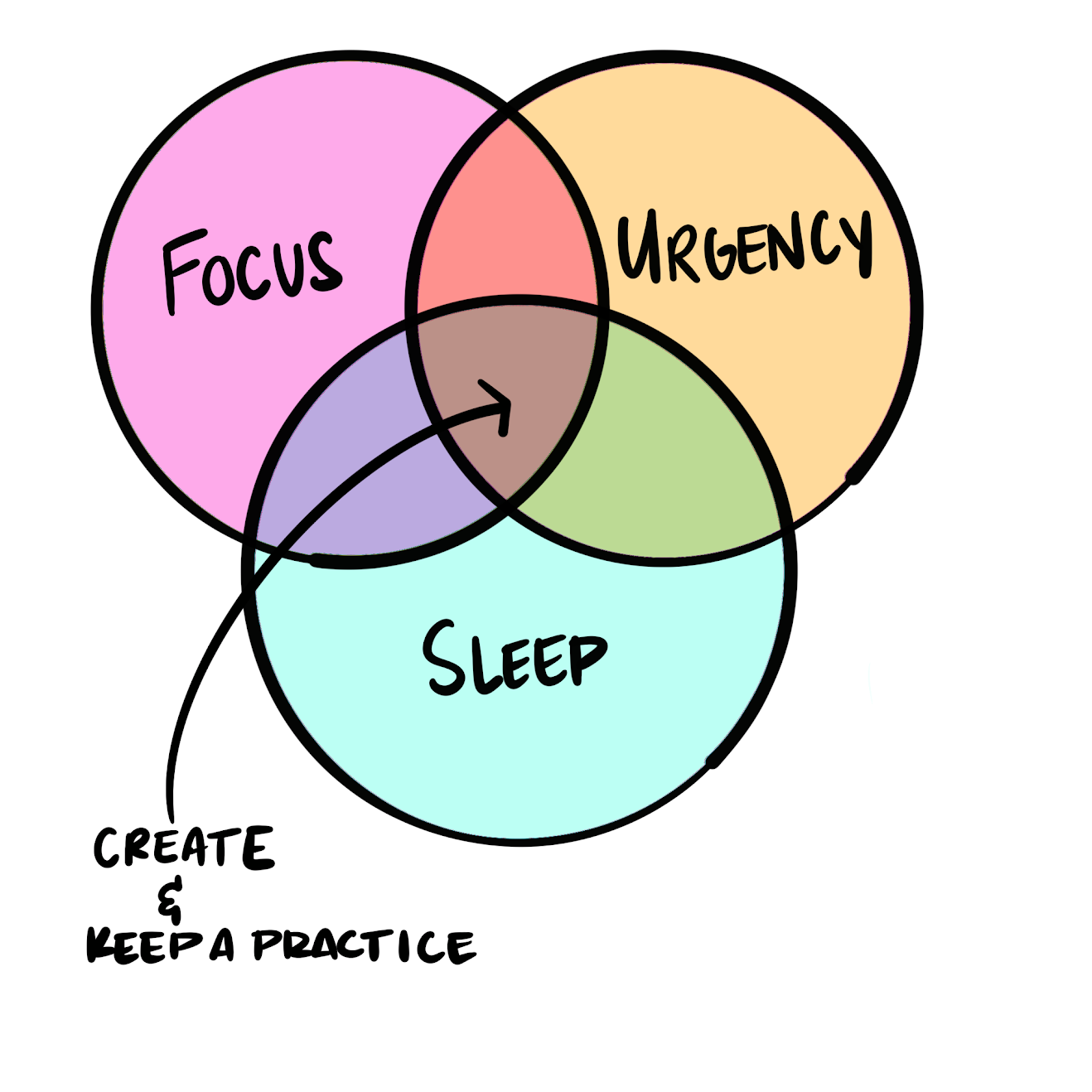

If we expand this out into the context of creating a practice or habit, being able to keep up with a practice requires three main things: urgency, focus, and sleep.

Why we quit

And that all leads us to why we quit. If that’s we need urgency, focus, and sleep to create and keep a practice, what causes us to quit? I literally cannot list the number of things I’ve quit. The list is long. The list is sad. And I feel so guilty about it that I even wrote an entire post about it a couple years ago.

What is wrong with me, I lamented, that I could never start a practice or project or habit and keep it up.

Well, now I’ve learned why.

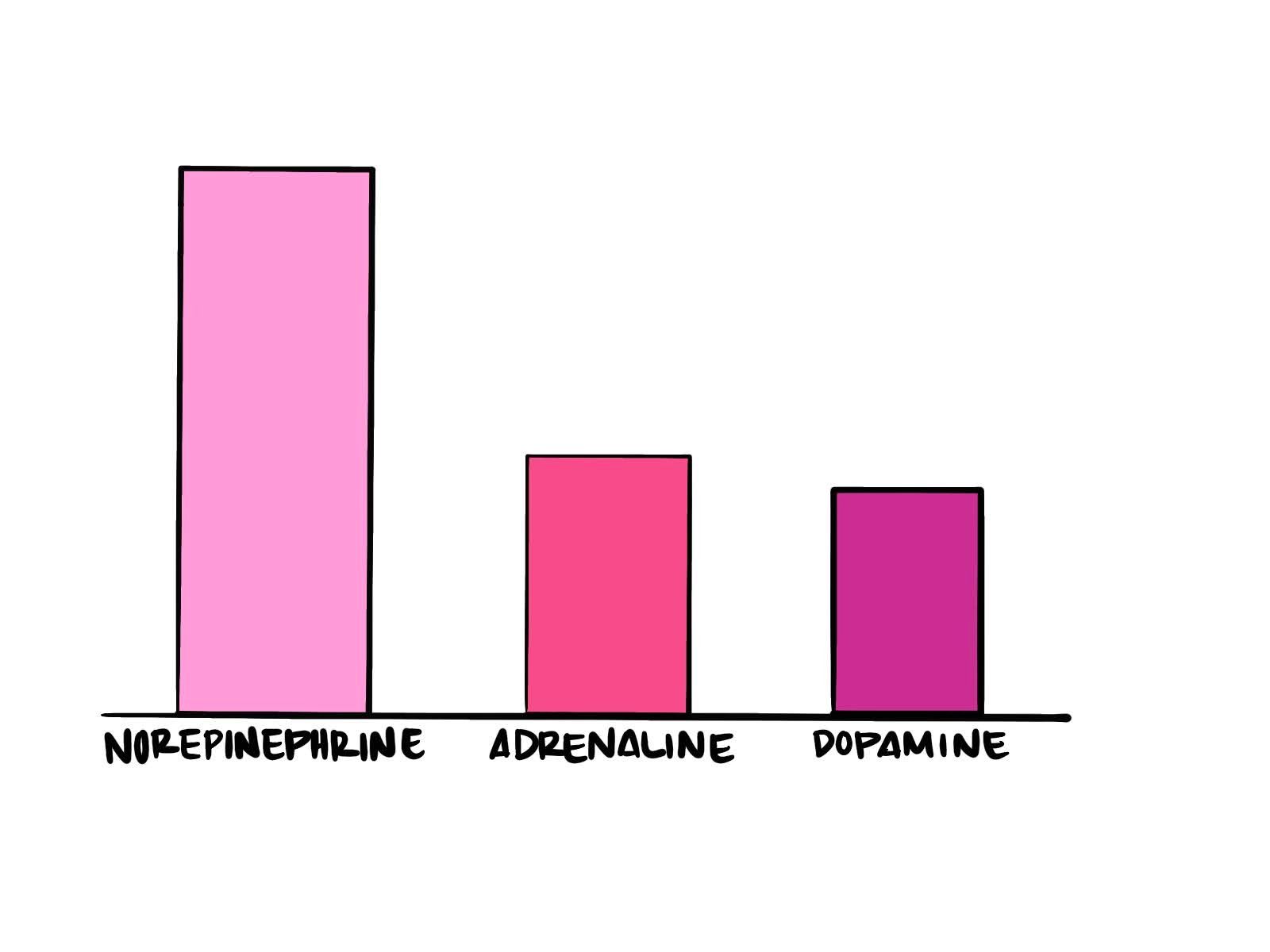

Anytime you try to focus and complete a task, your brain creates a stress response and releases three main hormones: adrenaline, norepineprhine, and dopamine. At a very basic level these hormones help us move through a task. Adrenaline incites movement, and gets us to start a task. Norepinephrine incites a stress response to keep us moving through it. Dopamine is released at the end of the task and helps us experience pleasure for completing what we set out to do.

We quit because our adrenaline, norepinephrine, and dopamine become out of sync. When norepinephrine becomes too high, that makes our brain unable to regulate the stress response. Without being able to regulate the stress response, our brain shuts down that task and makes it impossible for us to move forward.

Norepinephrine can get to high if we don’t get enough sleep, or if we aren’t breaking our tasks down in small enough pieces, or if we aren’t able to focus.

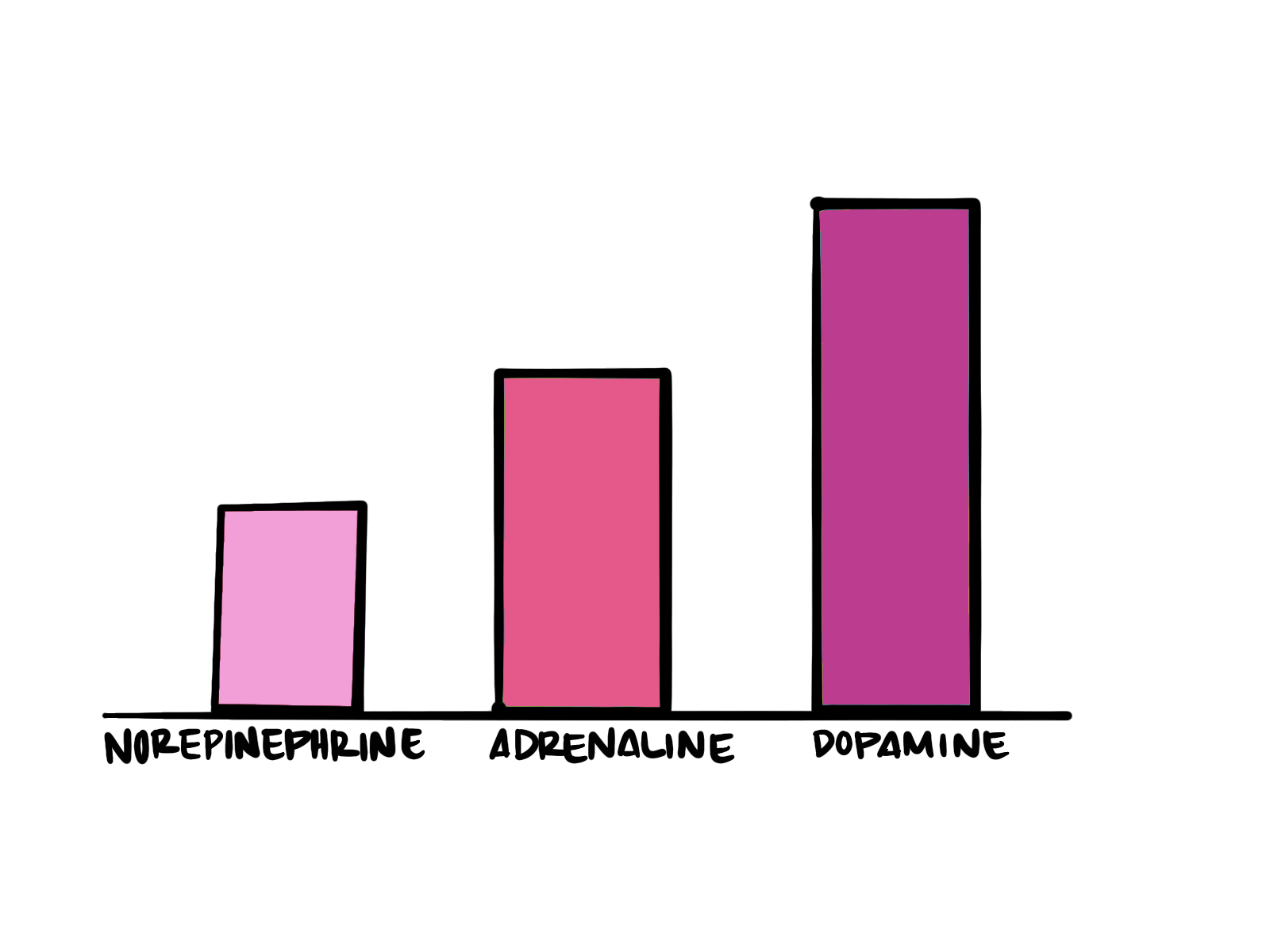

To counter the norepinephrine, you have to balance it out with more dopamine. And here’s the really tricky part. That dopamine needs to come in the form of an intrinsic reward. Setting an external reward is doomed to failure. If you want to really keep growing a practice, you must find a way to reward yourself just by completing the task.

Maybe that means breaking a task down into very small parts so you can feel a little bit of dopamine each time you finish something. When I wrote this blog post, for example, I broke it out into drawings, an outline, and then sections for the final post, which you’re reading now.

Breaking it out into smaller pieces meant that I felt really good when I finished anything that went toward the final post. Having small pieces I could work on helped me stay motivated to keep going. It also helped me assess duration, path, and outcome in different ways, and helped buffer the quit response.

Instead of thinking, I have a whole post to write, I thought, I want to finish this illustration. And once I did it my brain was happy with the progress I’d made. I’d created a path, assessed the duration, and completed the outcome.

Agitation is expected

Not to say that breaking things down makes everything easy and wonderful. There were days I didn’t want to draw illustrations, so I didn’t. There were times when I wanted to work on the outline instead, so I did.

I wouldn’t say that I enjoyed writing all of this. But I was motivated because I wanted to share something I learned, and I felt an urgency to do it. I live in an almost constant state of agitation like this. I want to do something, but I just feel generally uncomfortable about doing it.

And this the most important thing I learned about starting and keeping a practice:

Agitation is normal. Agitation is expected. Discomfort is normal. Discomfort is expected. And the only way to relieve that feeling is to work through it. You have to be willing to be agitated. It’s part of the process.

Learning this helped relieve me of so much pressure. It’s okay that I’m feeling uncomfortable. I just needed to create small internal rewards for myself along the way so that my stress response stayed balanced so I could finish.

That, and making sure to sleep. Sleep is so, so, SO important! But the way to make it through, the way to really create a new practice, the way to finish… is to just not quit. So do whatever you need to in order to maintain that balance.

Keep moving forward

Let’s talk a little more about discomfort. It’s important. It moves us. It makes us search and want and look for things. It really does keep us alive.

Much like a great white shark, we must constantly move forward. If a great white shark stops swimming, it will die. If we stop moving forward anxiety will settle in like dust. Forward action is rewarded at a neurochemical level.

Instead of trying to control your thoughts, instead of trying to reason your way through the discomfort, move through it instead. Literally. Get up and take a walk. Move your arms around. Shake your body. Bounce your legs while you’re sitting down. Dance. Do whatever your body allows you to do that is movement.

If you’re able to get outside and walk around, the forward action of walking creates lateral eye movement, which is a naturally calming response. But anything you can do to literally move your body will help unlock that sense of anxiety so that you can regroup and focus on something else.

Growing and becoming a better you

Always, but especially right now when we’re dealing with a global pandemic, social injustice, and the rising impacts of climate change, we all need to have more of a growth mindset.

We must learn to see what could be possible in a reimagined world. We must listen to the voices who have been telling us over and over again that change needs to happen.

How do we do this?

I think a piece of it starts with us, individually. Yes, we need the system to change. Yes, we need an overhaul and a global level. But we are all a piece of the system and I think it requires us to look inside ourselves and see what we need to do better.

We must learn to calm our autonomic nervous system. We do this through physiological sighs, movement, sleep, and compassion for ourselves.

We must challenge what we believe to enhance compassion. Avoiding challenge decreases our compassion. When we hear only those who agree with us, and it stunts our ability to learn. There is really no way for us to truly know the pain that others have felt, and there is a danger of complacency when we put on a blanket of empathy and say, “oh yes, I understand that now, because I’m empathetic.” But to grow we need to hear from other perspectives and take their perspective as truth and as a lived reality. Compassion helps us make better choices. Please note that I am not saying we should engage with people who are speaking in bad faith, who are looking only to incite argument, or who want to hurt people. What I am saying, is that if something makes you uncomfortable, ask yourself why and take that time to grow.

We can also practice gratitude and silence to feel better. Silence gives us the space to let our mind wander a bit. And practicing gratitude helps compel us to give back to others by engaging in reciprocity.

How I’m practicing these new things

I want to be better. I want to feel better. I want to live in a world where we’re helping and healing and cultivating instead of destroying.

So I’ve chosen some actions to help me grow. I pay a lot of attention to the amount sleep I get and try to go to bed at a reasonable hour every night so I can get a full night’s sleep.

I practice moving forward by literally exercising and going on at least one walk every day to help me focus.

I practice finishing by setting small, tiny, goals for myself and completing them. And then I tell myself how happy I am that I completed the thing.

Every day I sit outside or by a window in silence with no phone, nothing, for at least a 5 minutes. I let my mind wander wherever it wants to go. If a negative thought comes up I let it happen. And then I think of something I’m really grateful for to balance out the thought. Sometimes it’s a hard day and I cry. That’s okay, too.

These actions have shifted how I feel. 2020 has been a hard year, and I honestly think things are going to get harder before they get better. I’m done trying to control how I think or how I feel. I’m done trying to control my anxiety. Controlling the mind is hard. Start with behavior, and your mind will follow.