How Bees See the World

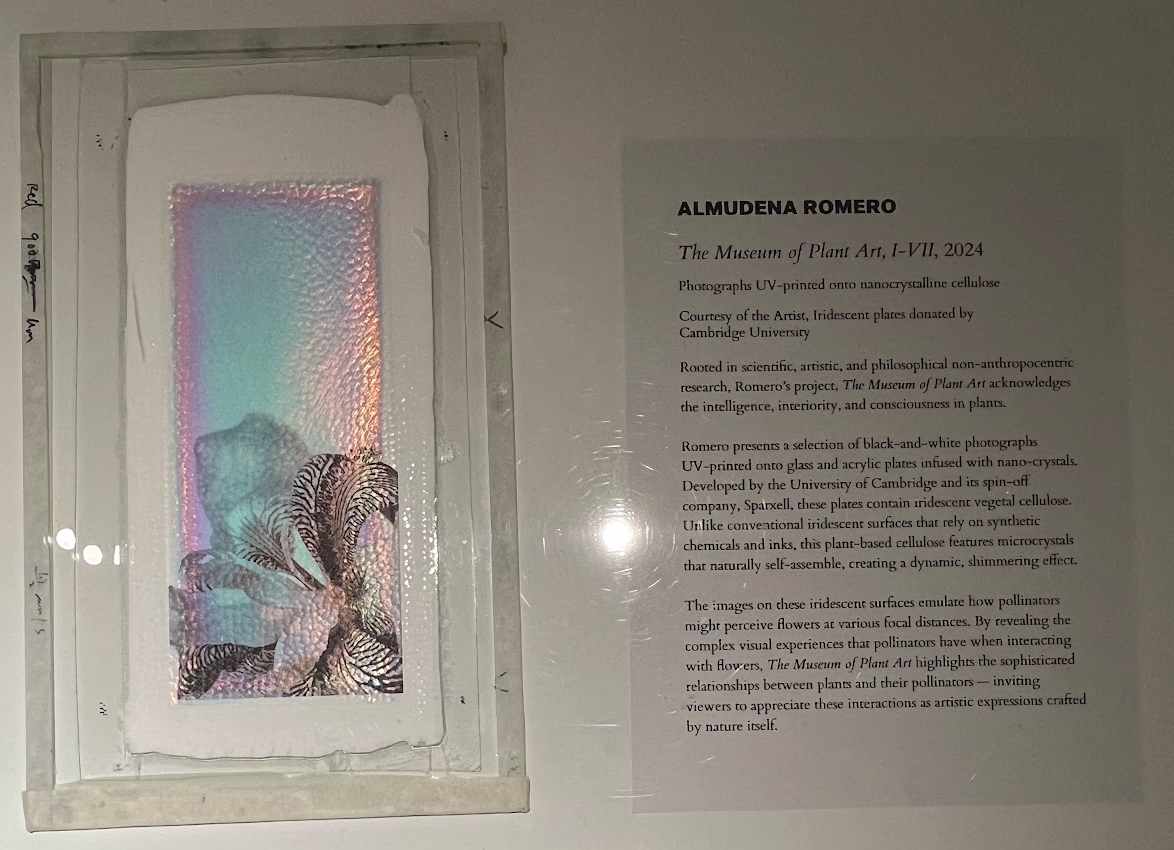

I recently went to the Saatchi Gallery in London, and they had a whole exhibit on flowers in contemporary art. One image that caught my eye, and made me want to write this article, was this. It’s a UV image of an iris, an exploration on how a bee might see a flower. For years I’ve been curious about this. How do other animals see the world? What can they see that we don’t, and vice versa?

Every morning from the cool, early days of spring to the cool, last days of fall, I sit in my garden and watch the bees. My neighbor has honeybees that lazily move through and I plant native wildflowers to attract the native bumblebees. I love all the colors that rise up during the season, the violet lupine, the orange poppies, and the delicately pink bleeding heart. But as the bees and I share the garden, me watching as they hover intently around the flowers, I wonder, do they see the garden the same way I do?

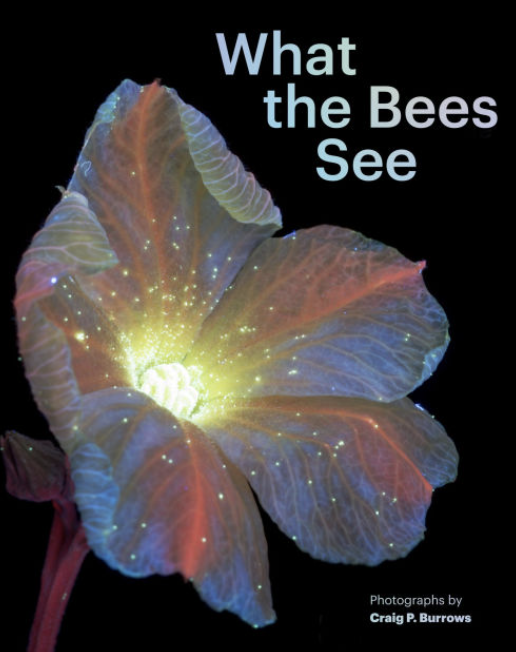

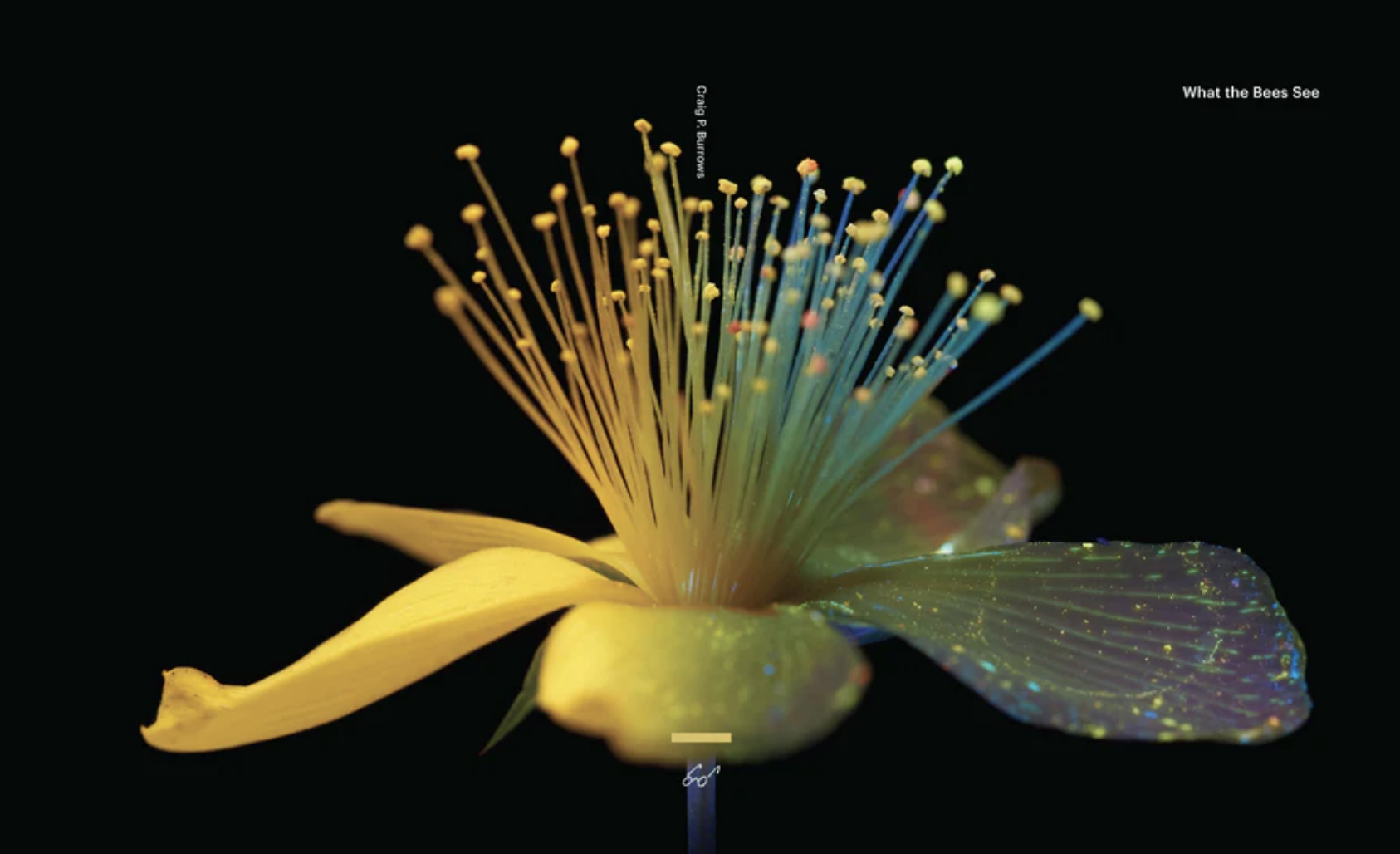

The book What the Bees See: A Honeybee’s Eye View of the World by Craig Burrows, suggests that although we share the same space in the garden, we don’t see the same things.

Here we are, living on the same planet, side by side, in two completely different worlds.

How color works with our eyes

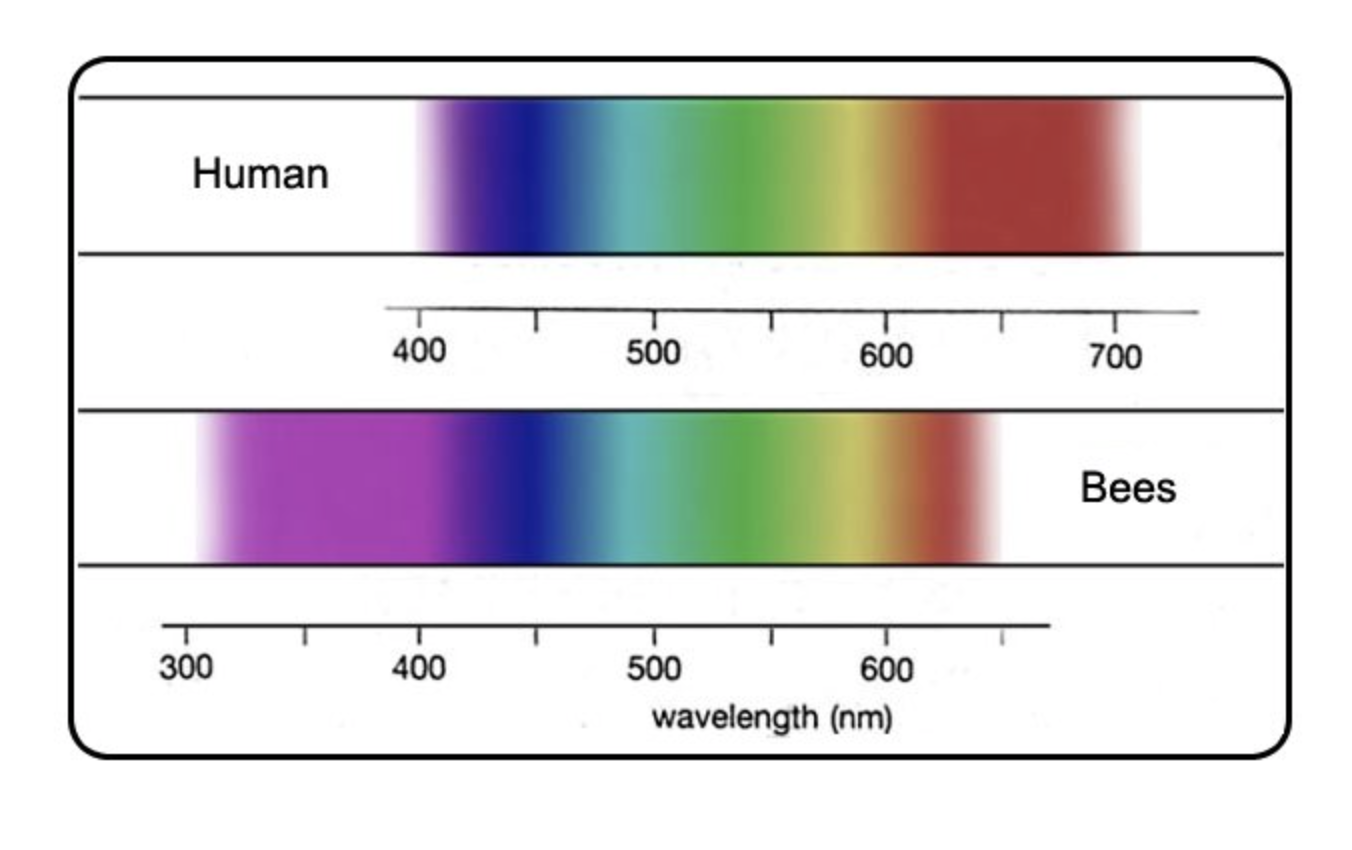

In a previous newsletter, I’ve talked about how color works. But how does an eye perceive color? Animals that can see color have photoreceptors in their eyes. In humans, that translates into rods and cones. Rods allow us to perceive light and periphery vision and cones allow us to perceive different color waves. In humans, we have three cones that can perceive red, blue, and green. Every color we perceive is a single color or combination of more than one color.

With our 3 cones humans are able to see around a million colors!

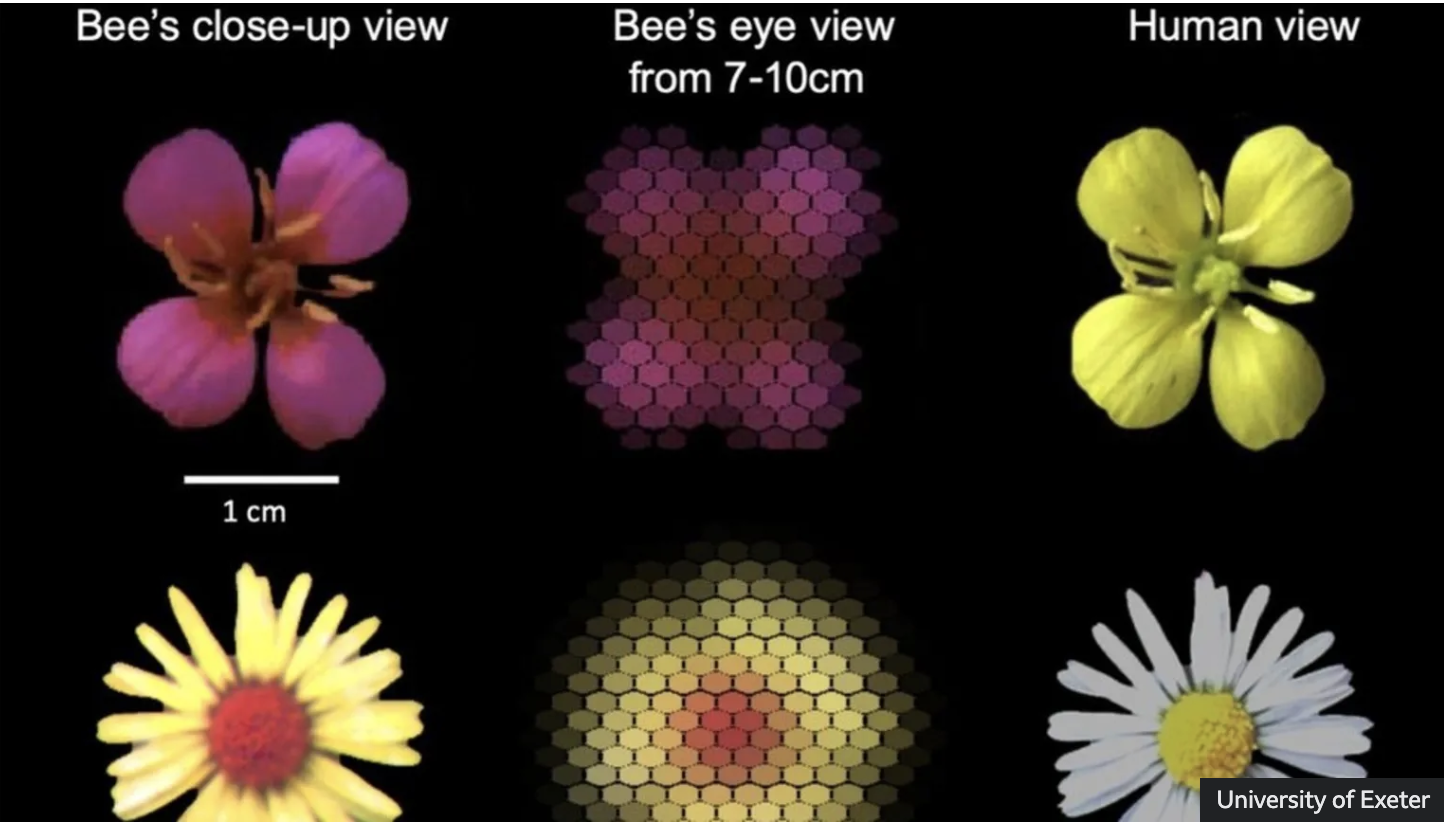

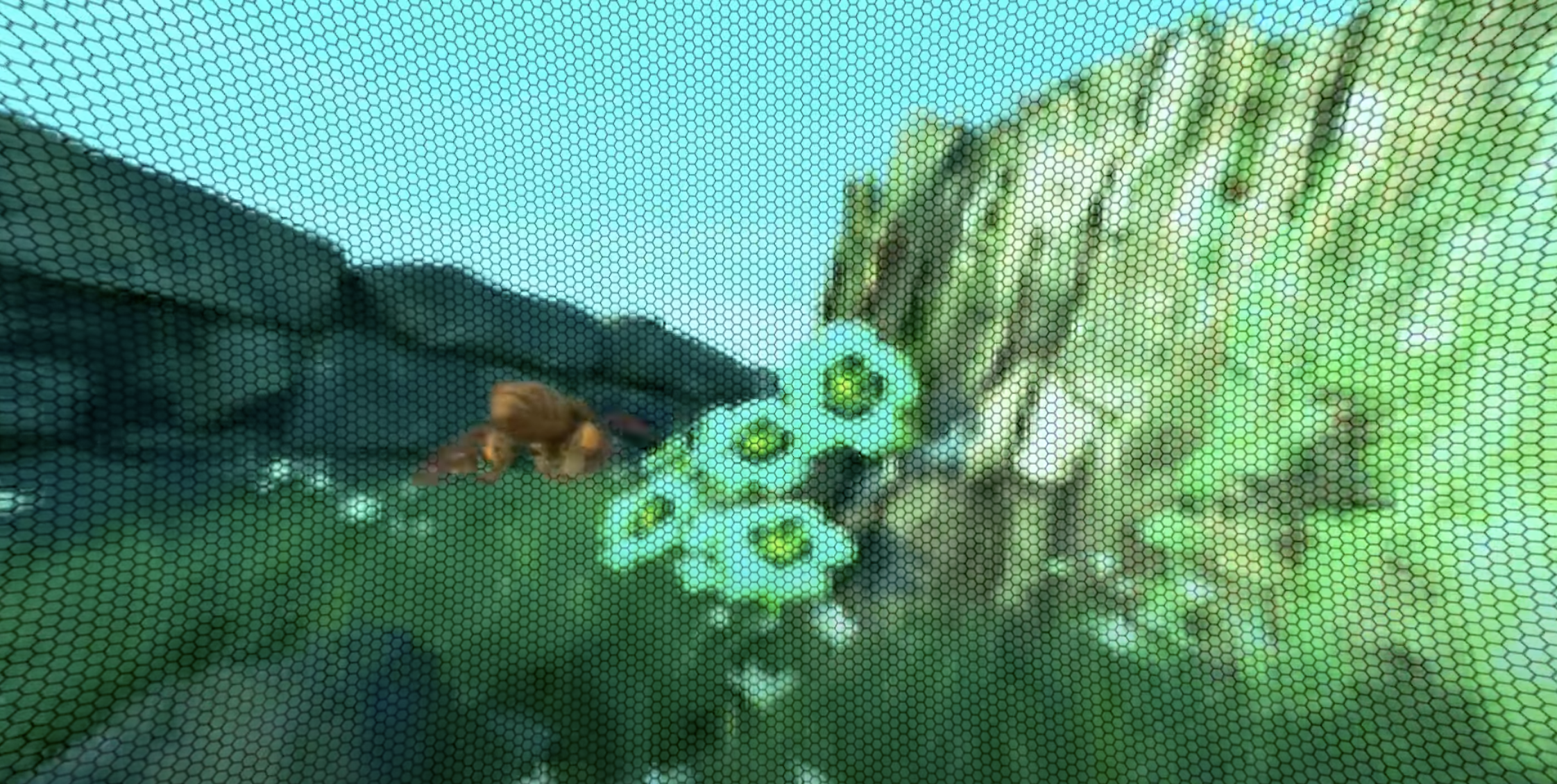

Bees have compound eyes made up of individual ommatidia. Scientists currently think that bees see in a pixelated way, with a higher resolution image the more omatidia they have. Bees can also see polarized light, creating a band running across the sky like a stripe,90 degrees from the sun. Bees use this polarity to navigate. They can also see color, but their visible range is yellow, blue, green, violet, and ultraviolet. Their visible color range is shorter, but they can see ultraviolet light, and so the world looks very different than what we see.

Science is also emerging suggesting that pattern plays a huge part in how a bee finds flowers, and that they can differentiate different flowers by their patterns, even from far away. Due to the nature of their eyes, bees can’t see a sharp image of what’s in front of them until they get really close.

Additionally, some flowers likely have UV reflective areas on their petals, to help “guide” the bee to the pollen by creating a very obvious center, almost like a bulls-eye.

What a bee sees

In a study conducted at the University of Exeter, scientists are beginning to think that patterns, and not just color, are important for bees to tell different types of flowers apart. You’ll notice that the pattern is distinguishable even when the image is still pixelated.

You’ll also see that the color is represented differently in the “regular” photo vs the UV image. The colors above are likely not the colors that the bee sees, but these images help us understand the patterns and pixelation.

You’ll also see that the color is represented differently in the “regular” photo vs the UV image. The colors above are likely not the colors that the bee sees, but these images help us understand the patterns and pixelation.

For a better grasp of the colors they see, we need to look again at Craig Burrows work. Here, he shows that a flower that looks white to us likely looks violet to a bee.

And here on the left, a simple, but beautiful yellow flower to us, almost glows when seen by a bee.

This video is also really fascinating and explains how bees might see the world: a world shifted into a more blue-green spectrum, with a dark strip of blue polarity across the sky to help them navigate, and flowers with vibrant patterns that invite them to come and land.

I have a lot of bees in my garden, which tells me that overall, it must be pretty eye-catching—even if what I’m seeing and what the bees are seeing are nowhere near the same thing.